Running the Bases: What MLB Stats Suggest About Wiffleball Ghost Running

One of the earliest articles describing competitive wiffleball games that I have come across is from a July 1968 edition of the Southern Illinoisan newspaper. The article describes a one-on-one tournament in Carbondale. The participants were exclusively children, but nonetheless the tournament reads a lot like the kind of backyard wiffleball one might find today. Like most articles on competitive wiffleball, this one spills a lot of ink on the rules, particularly when it comes to the utilization of “imaginary” baserunners. The writer makes note that on a single – a ball hit past the pitcher’s mound – a runner on first moves to second while a runner on second base scores. According to the article, on a double all baserunners score.

Gelman, B. (1968, July 28). This is Baseball? Kids Like It. Southern Illinoisan. Pg. 8.

While not explicitly stated, it stands to reason that the kids wished to simulate the typical movement of base runners in baseball with their wiffleball rules. In their minds, baseball players usually scored from second on a single and players usually scored from first on a double. They adopted rules to simulate the relative frequency of those occurrences. In subsequent years, many larger wiffleball organizations also tackled base running by using Major League Baseball as a guide. Often, the main goal of non-base running wiffleball rules is to provide a facsimile of baseball. That includes advancing runners in line with how they would advance in a major league game.

There is a general consensus among historical (defined here as pre-2000) and contemporary competitive wiffleball rule books as to how runners should advance in these scenarios. The 1989 (and subsequent) World Wiffleball Association (“WWA”) rule books called for runners to move one base on a single, two bases on a double, and three bases on a triple with less than two outs (more on that caveat in a bit). Jerome Coyle’s “King’s Rules” – which were originally dreamt up in 1981, codified in 1985, and influenced many rule books that are around today – called for ghost runners to “automatically advance the same number of bases as the batter.” The preface of the King’s Rules specifically listed that the main objective is to “imulate (sic) baseball”. The New Jersey Wiffleball Association rule book – crafted from the WWA rule book – also called for the imaginary runners to move in lockstep with the batter. The rules of the North American Wiffleball Championship in Cincinnati (1995-1997) were influenced by the King’s Rules and as such, runners moved as many bases as the batter. The overwhelming majority of subsequent organizations, including current non-base running organizations, have runners advance on doubles in a similar fashion. There is an obvious consensus that has been formed over the past three decades.

There is also a consensus among these sets of rules on how a runner should advance from second on a single. Once again, the historical competitive wiffleball rules run opposite of rules used by the kids in Illinois in 1968. While runners scored from second on any single in their games, all of the aforementioned rule books advanced a runner on second to third on any single with less than two outs.

If emulating baseball is the chief concern, then which party has it right – the kids from Carbondale or the vast majority of historical and contemporary non-base running rulebooks? That question can be answered quantitatively.

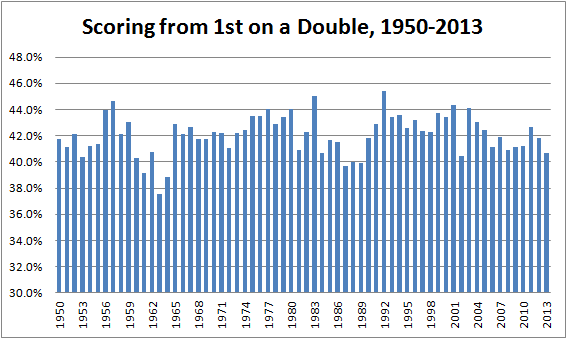

In April 2014, Scott Lindholm of the baseball analytics blog Beyond the Box Score contemplated how often a runner scores from first on a double after slow-footed Adam Dunn was thrown out trying to score on an Alejandro de Aza double against the Red Sox in an early season game. Using data compiled from Baseball Reference between the start of the 2009 season and the first month of the 2014 MLB season, Scott calculated how often a runner scored from first on a double on a percentage basis. He also categorized the hit data by where the double was hit.

The data showed that runners scored around 40% of the time on doubles hit to left field, approximately 35% of the time on doubles hit to right field, and approximately 55% of the time on doubles hit to centerfield. Lindholm addressed the variations logically – right fielders tend to have the strongest arms among outfielders and doubles hit to center tend to be in the gaps where the ball travels the longest distance – before drawing a broader conclusion. The data – which he expanded to include all seasons between 1950 and 2013 – shows clearly that runners score from first on a double less than half the time. During that time frame, runners never scored from first on a double at a clip greater than 46% in a season with the average somewhere around 42%.

Reposted from “Scoring from first on a double: easier said than Dunn?” (Scott Lindholm, Beyond the Boxscore - April 21, 2014).

While those success rates have varied a little season to season, they have not varied significantly and the outliers tend to be towards the lower end (the success rate dropped below 40% for at least a couple of years in the early 1960’s, as one example). For Major League Baseball in 2018, a double was hit with a runner on first base 2,633 times. The base runner scored 1,110 times in those instances, which is a 42% success rate. That is right in line with the historical average.

Frequency a runner scored from first on a double during the 2018 MLB season.

What this data tells us is that in the major leagues, the odds of a runner on first base failing to score on a double are roughly 3:2. If the only goal of a non-base running wiffleball rule book is to simulate the play found in Major League Baseball, then moving the runner from first to third on a double is the best decision.

As the Beyond the Box Score analysis showed, it would be within the spirit of emulating baseball to allow for a double to centerfield to score the baserunner from first since that happens almost 60% of the time. Of course, that also creates another judgement call which wiffleball rule books generally like to avoid as much as possible.

(Some organizations – most notably the WWA and NJWA – did seem to recognize that base runners were more likely to take an extra base on a double to center than they were on a double hit to right or left. Both organizations incorporated rules that called hits off the centerfield portion of the outfield wall “triples”, which in turn allowed the runner from first to score. While not exactly the same as writing a rule that allows the runner to take an extra base on a double, the intent is similar.)

Doubles not only differ by where they are hit and how hard they are hit, but also by other situational circumstances like the number of outs in an inning. General baseball wisdom states that runners gain an advantage with two outs because the runner can move on contact without fear of being doubled up on a caught fly ball. With one out, a runner on first will pause until he feels that the ball is likely to fall in for a hit. With two outs, that same runner can put his head down and run full speed ahead the minute the ball leaves the bat, knowing that if it is caught the inning is over anyway. Things are murkier with ground balls – there are situations where a non-forced runner might want to stay put for a moment even with two outs – but that is irrelevant to any discussion about a runner on first base.

Using situational data from Baseball Reference for the 2018 MLB season, the likelihood of the runner scoring on a double is approximately 42% without regard to outs in an inning. That percentage jumps to approximately 54% when there are two outs in an inning when the double is hit. While this is a relatively small sample, it supports the notion that runners are more likely to take an extra base with two outs than they are with less than two outs. That is one old baseball axiom that holds up under scrutiny.

Astute wiffleball rule makers noticed that to be true and have long included provisions that allow all base runners to move an extra base on any hit (not just doubles) with two outs. As early as the mid-1980’s, the World Wiffleball Association utilized such a provision by stating that “with 2 outs all runners go 1 extra base on a clean (untouched) hit.” King’s Rules did not allow baserunners to automatically advance in that situation. Perhaps because of the heavy influence the King’s Rules had on the North American Championship, those tournaments also did not allow automatic extra advancement with two outs, either. The NJWA rulebook – which was based off the World Wiffleball Association rulebook – provided the extra base with two outs. Most current organizations utilize some form of that rule by either allowing an extra base on all hits with two outs or allowing a run to score on a double with two outs. The numbers suggest that it is an appropriate rule if the goal is to simulate a typical baseball base running movement.

What about runners scoring from second on a single with less than two outs?

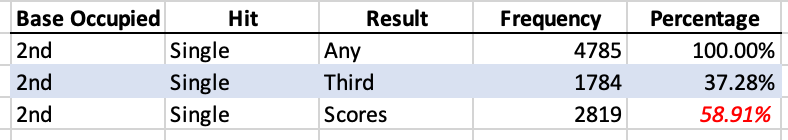

Frequency runner scored from second during the 2018 MLB regular season.

In 2018, runners scored from second on a single – regardless of the number of outs – 59% of the time. That data would appear to indicate that the kids had it right and that most 2018 non-running wiffleball rule books failed to properly simulate that aspect of baseball.

Of course, there is more to wiffleball baserunning rules than merely emulating baseball. There is something to be said for simplicity, particularly since non-base running wiffleball rules tend to be rather complicated as is. Requiring players to remember a specific base advancement scenario – rather than simply stating that the runner moves the same number of bases as the batter with less than two outs – may not be worth the benefit.

It could also be argued that aside from better aligning with baseball, such a rule change would not benefit the game in any other way. That rule would not increase offense or action. The same amount of offense/action – a batter hitting a single – occurs regardless. All it serves to do is artificially drive up the number of runs scored over the course of a season.

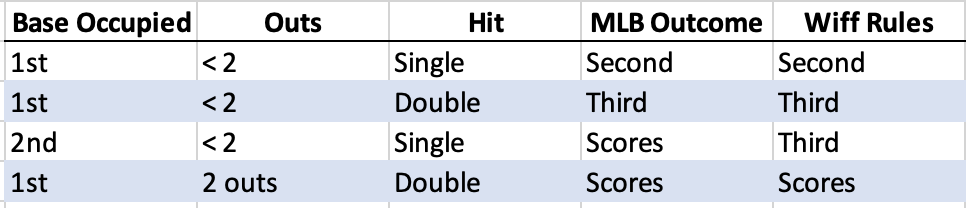

How base runners advance the majority of time in MLB compared to the majority of non-base running wiffleball rule books.

To summarize, if the only goal - or the main goal - of runner advancement rules in wiffs is to emulate the most likely MLB outcomes, then runners on first should advance the same number of bases as the batter with less than two outs, a runner on second should score on a single regardless of the number of outs, and a runner on first should score on a double with two outs.

![[MAW] 2019 Winter Classic: All Nighter Tournament Recap](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bc107b5523958c1f9507359/1550249739523-253F222KZQ83QBY9VI17/The+Best+Haircuts+of+2020.png)

![[DROP 100] The Drop 100 for 2019: #25 - #11](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bc107b5523958c1f9507359/1574783709691-HM95S4C4SKOWG4WH8EO6/Drop+100+%235+%281%29.png)